Divine Evidence?

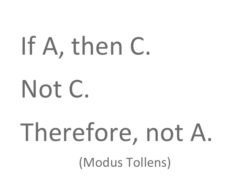

The most often-cited motivating reason to not believe in God is the absence of quantifiable, valid evidence that He exists. In propositional logic, the reasoning goes:

- If God exists, then there is evidence of it.

- There is no evidence for God’s existence.

- Therefore, God does not exist.

This argument is indeed valid, because it uses modus tollens—given a conditional statement and the negation of the consequent, the antecedent must be false. However, it is not sound, starting with the first premise, as God could have the power to hide evidence of his own existence. Moreover, the second premise is questionable, because when considering evidence, the positive atheist faces even greater hurdles than the theist.

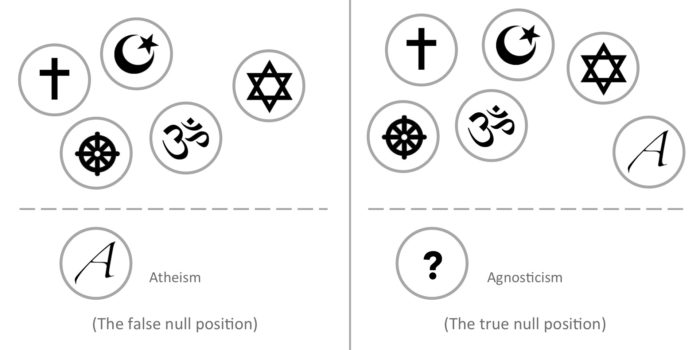

The positive atheist faces issues of evidence, because positive atheism is also a declaration just like theism, and must therefore be defended, too. Consequently, it also has a burden of proof. This burden seems counterintuitive, at first glance, because it seems like atheism is a “null” position compared to the religions of the world. Rather than asserting which gods are real, it’s position is that there are no gods. However, this position is not the same as the denial of theism, which does not incur a burden of proof. Philosopher T. Edward Dame makes this clear with his assertion that denying a belief is different from asserting its falsehood, the latter of which has a burden of proof. To see this distinction more vividly, the atheist personality Matt Dillahunty is very helpful with his example of a jar with balls.

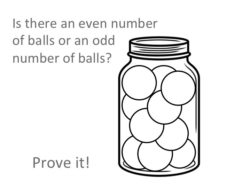

There are two claims about the number of balls in the jar and only one can be correct: either there is an even amount or odd. You can make claim about which one it is, but then you will need to prove you are correct. Dillahunty reveals that the only true null position, with no burden of proof, is to “suspend belief in both [positions],” or to not make any claim. The truth about positive atheism is that it makes one of two such claims—namely, that God does not exist. The only position that does not have a burden of proof is agnosticism, which “suspends belief” in both positions concerning the existence of God.

Moreover, positive atheism has a higher burden than theism; because in order to fully argue that a claim is false, the atheist has to prove that there is no evidence anywhere that could prove the claim is true (for example, to prove that apples do not exist, someone would have to search the universe to ensure there are no apples anywhere or prove that the universe does not allow apples to exist). The theist only has prove that this universe is a universe made by a god, which is a daunting task, but less so than the atheist.

The second premise is furthermore troublesome because it begs the question—namely, whether any evidence for God’s existence has been detected. Many people argue that this evidence has not been found, but their argument might merely reflect what kind of evidence they want, versus the evidence we actually need. If one is looking for evidence of God in the form of a literal man in the sky, then they are only going to justify their skepticism, and, on the other hand, if the evidence for God is the universe itself, then the evidence is tautological and scientifically untestable. The question of divine evidence therefore relies on who is qualified to find and evaluate it. As Irving Copi—student of Bertrand Russell—wrote, “In some circumstances it can be safely assumed that if a certain event had occurred, evidence of it could be discovered by qualified investigators. In such circumstances it is perfectly reasonable to take the absence of proof of its occurrence as positive proof of its non-occurrence.” But whom should we count as these “qualified investigators?” Given, that scientists study the observable universe, they are not likely to detect traces of an immaterial being, such as God. Therefore, given that we may neither have the tools nor the minds to (secularly) find God, we cannot say that there is no evidence for His existence. We must take the position of the observer in Dillahunty’s jar example, and suspend belief until further notice.

References:

Copi, Irving M. Introduction to Logic. 4th ed. New York: Macmillan, 1972. Print.

This Philosophy post was written by Princeton.

Comments